Introduction

This article presents the first part of a study on how the automatic speech recognition (ASR) system of the Portuguese Parliament may influence the grammatical correction of plenary reports.

We will briefly present the Portuguese Parliament’s official journal, our editing workflow, our ASR system, and the hypothesis of this study, as well as our first findings on how some specific Portuguese syntactic structures are edited, or not, in the production of our report.

Producing DAR

As in other parliaments, the specific work of the Official Journal Division (OJD) of the Portuguese Parliament involves producing the Diário da Assembleia da República (DAR), the Journal of the Assembly of the Republic, which consists of a substantially verbatim transcript of plenary meetings. This report includes the Members of Parliament’s (MPs’) speeches, and administrative and procedural information, as well as interruptions, noted manually by reporters and editors during the meetings.

Reporters work in the chamber, in 15-minute shifts, noting interruptions, applause, and other non-verbal events, which they later include in the report. The report’s production involves three main editing stages: 1) the reporter stage, in which reporters use STAAR (Sistema de Transcrição Automática da Assembleia da República, Automatic Transcription System of the Assembly of the Republic), our internal ASR system, together with audio and video, to transcribe their segment, incorporate notes, and review the text for accuracy in names, legal references, terminology and standard formatting; 2) the editor stage, in which the editor compiles the previous segments, reviews them, adds more interruptions and expands acronyms; 3) the draft stage, in which all parts are compiled. The draft version is first published on the intranet, and only after a final review is the official journal approved in a plenary meeting.

STAAR and the production of DAR

After a long process testing different ASR systems, our OJD began to use, in April 2023, a system based on OpenAI’s Whisper. This is an AI Large Language Model specialised in transcription (Granja, 2023). With our collaboration, our IT department developed the system STAAR. This system enables Whisper to automatically transcribe the meetings’ audio recordings. It recognises when the speaker changes and applies replacements and formatting, streamlining the entire process (Nascimento, 2024).

STAAR is most relevant in the first stage of editing the journal. Indeed, most reporters have been using it since it was implemented, as the initial word error rate was well below 2% for pre-written and well-articulated speeches. Consequently, reporters are now presented with a text in MS-Word, and they no longer have to type from scratch. Reporters still have to identify speakers, remove unnecessary elements, add administrative or procedural information, include relevant non-verbal events and edit the text for coherence and clarity. However, this now amounts to a preliminary review rather than a full manual transcription.

Research hypothesis: the influence of STAAR on producing and editing DAR

Scholars have noted that fewer editorial interventions are made in official reports today. Eero Voutilainen (2023), for instance, showed that, in earlier times of reporting, more changes were made. The author gives three reasons for this: i) there were no video or audio recordings of the debates for comparison; ii) there was a need to make speeches sound more elevated; iii) there was less awareness of linguistic variation. Now, the opposite applies. As the author mentions, this may happen for three reasons: i) readers can compare the debates and the written speech with video and audio recordings; ii) the idea of perfect parliamentary speech has faded; iii) editors are better trained to recognise syntactic structures in which grammaticality is dubious.

Our study aims to investigate whether STAAR changes reporters’ attitudes when transcribing speech into writing, leading to fewer edits. We want to understand whether using an ASR system leads editors to be more inclined to accept specific linguistic structures whose grammatical correctness is questionable. Consequently, the final report will resemble oral discourse more closely, with less grammatical revision, resulting in a more verbatim transcription.

Method

To determine whether STAAR is leading reporters and editors to perform fewer edits, we first identified some less obvious or unnecessary changes introduced when transcribing plenary session speeches into the final written version of the report. Given the high accuracy of Whisper’s original transcriptions, the documents produced by STAAR, without any human interference, provided an ideal “searchable” sample of MPs’ oral speech against which the written version could be compared. We examined all STAAR transcriptions produced between 24 March 2023 and 17 July 2025 and compared them with the final version of the report. However, given the number and variety of changes made, beyond grammatical and orthographic corrections, we had to restrict our analysis to a set of specific linguistic cases.

To this end, we selected 10 Portuguese syntactic structures representing three major types of linguistic problems (see below for the note on linguistic glosses):

- omission or addition of prepositions in verb complements, namely in verbs concordar com (‘to.agree with’) and discordar de (‘to.disagree with’) with phrasal complements, as well as with the verb tornar-se (em) (‘to.become’);

- misplacement of pronouns in verbal complexes —e.g. ??lhe gostaria de dizer (‘??dat.pron would.like to say’) vs. gostaria de dizer-lhe (‘would.like to say-dat.pron’) —or cases of pronouns placed after the auxiliary/modal verb instead of before the main verb — e.g. ??vou-lhe dizer (‘??will-dat.pron say’) vs. vou dizer-lhe (‘will say-dat.pron’);

- the use of the sentence-initial infinitive expression dizer que (‘to say that’), instead of e.g. quero dizer que (‘I want to say that’).

These syntactic structures currently lie on the borderline of ungrammaticality. Although traditionally regarded as incorrect from a normative or prescriptive perspective, they have become increasingly common in contemporary speech. Therefore, these are not necessarily considered wrong from a descriptive linguistic standpoint. This variation extends to MPs, reporters and editors alike. The final data consisted of 729 utterances from 198 sittings which we focused on when we compared the initial and final version of the report.

Preliminary results

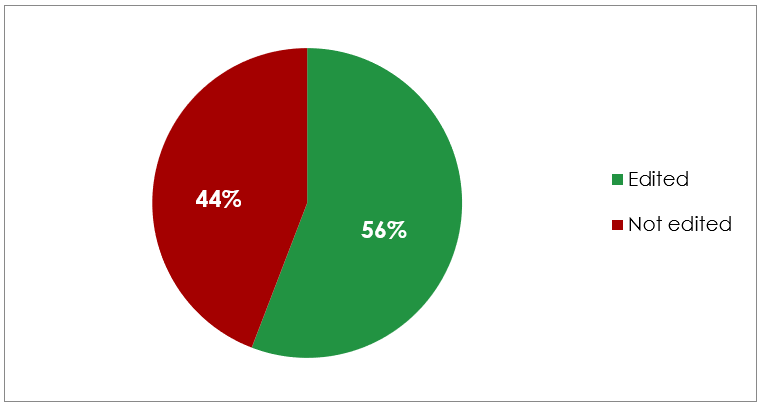

Examining the data, it is noticeable that, following the implementation of STAAR, the linguistic structures under consideration are still not accepted by the reporters and editors. In most cases, a larger proportion of sentences in our dataset were edited in the final report (figure 1), which apparently contradicts our initial hypothesis.

However, these preliminary findings indicate that the extent to which ungrammatical or borderline structures are corrected varies considerably depending on the specific structure involved (in the next part of this study, we will show how exactly these specific structures are altered by reporters).

In fact, for several of the examined structures, we would expect a substantially higher rate of correction, as they clearly deviate from prescriptive norms. This might suggest that editors are increasingly tolerant of oral linguistic features, or at least less inclined to normalise them, when producing the official written record. Still, caution is warranted on this conclusion, because our results may reflect sample-specific factors rather than a real shift in editorial practices.

To confirm this seeming trend of fewer-than-expected edits, and to determine whether it is due to STAAR, we will need to collect transcript samples from before STAAR and compare them with the present findings. This will be the next step in our study, which we hope to carry out and share with you soon.

Ana Rita Pereira and Paulo Granja work as parliamentary reporters at the Official Journal Division of the Parliament of Portugal.

Note on linguistic glosses

On Method section, we use a simple form of linguistic interlinear glosses, to transpose the structure of Portuguese verbs into English. Adapting Leipzig Glossing Rules, the Portuguese verb is directly translated to English, and the abbreviated grammatical category label “dat.pron’ renders the Portuguese pronoun “lhe”. When a single Portuguese word is rendered by several English words, these are separated by periods (e.g. concordar — ‘to.agree’).

References

Granja, P. (2023). The Portuguese Parliamentary Reporters’ Experience with Automatic Speech Recognition Systems. Tiro 2/2023. URL: https://tiro.intersteno.org/2023/12/the-portuguese-parliamentary-reporters-experience-with-automatic-speech-recognition-systems/

Nascimento, P., J.C. Ferreira & F. Batista (2024). Automatic transcription system for parliamentary debates in the context of assembly of the republic of Portugal. Int J Speech Technol 27, 613–635. URL: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10772-024-10126-4

Voutilainen, E. (2023). Written representation of spoken interaction in the official parliamentary transcripts of the Finnish Parliament. Frontiers in Communication 8: 104779. URL: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/communication/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2023.1047799/full

[…] Ana Rita Pereira and Paulo Granja:The Influence of AI on Grammatical Correction in Portuguese Parliament Plenary Session Reports — F… […]