One of the most dominant concepts in translation studies is the so-called translator’s invisibility (Venuti 1995). According to the theory behind it, fluency of translation predominates over other dimensions of quality, such as an accurate rendition of the culture implied in the translated text. By “culture”, Venuti means regional or social accents, colloquialisms, slang, obscenity, archaism, neologisms or so-called realia—words or expressions specific to a culture, including private and common names related to a specific society, such as fjord, empanadas, bidonville, duma, Ku Klux Klan, Kalashnikov, Beaujolais, etc.

In this context, acceptable translations which are consistent with the reader’s culture are preferred to adequate translations that are close to the original text. From this derives the well-known Italian motto “traduttore traditore” (“translator traitor”, when preferring a beautiful translation to a faithful one), which mirrors the French motto belles infidèles (“beautiful unfaithful”), a concept opposed to that of “faithful” translations, seen as stylistically ugly. Belles infidèles produced by traduttori traditori purposely erase all traces of foreignness or alterity in the original text. By doing this, the translator disappears, as if the translation was written by the same author as the original text.

In professional reporting, this notion of translator’s invisibility can be seen at a different level. If a report is a speech-to-text “translation” of what is said by the speaker, the notion of quality the reporter follows may turn his or her role into a more or less visible one: the more verbatim a report is, the more visibility is given to the reporter. In this case, the report meets the expectations of the reader, because it exactly mirrors what the speaker has said, but jeopardises readability, as a transcription of an unplanned speech can sometimes be difficult to immediately understand. Conversely, the more sensatim a report is (i.e. reporting meanings instead of every single word), the less visibility is given to the reporter. In this case, the reader has the impression that the author of the report is the speaker himself or herself but jeopardises accuracy, because it runs the risk of misinterpreting the speaker’s mind or of correcting his or her grammar.

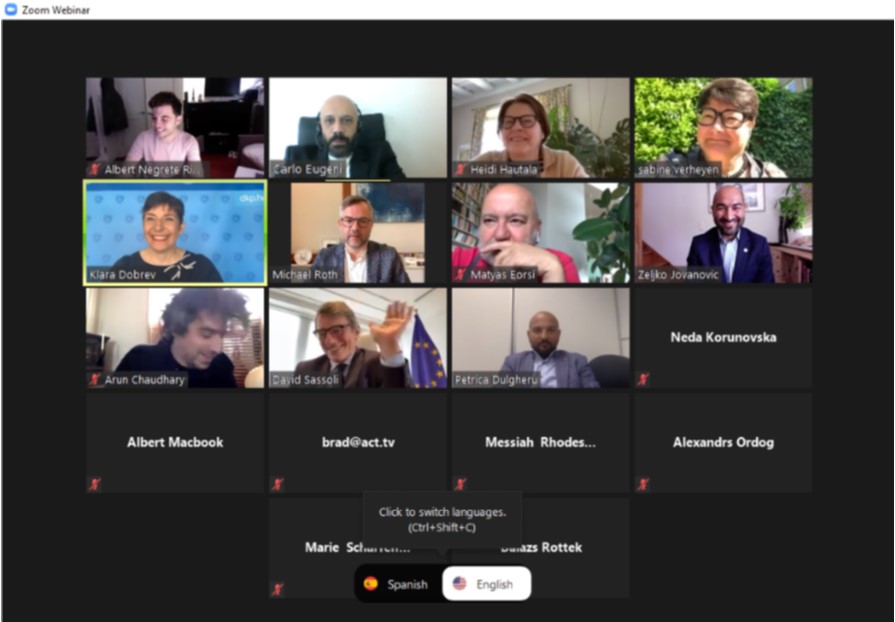

On top of this linguistic aspect, a social aspect of visibility has emerged during this period of social distancing. Because of restrictions, many professionals have worked from home (see contributions by Eras, Dibelka, and Eugeni in this issue). In the case of live reporting, the professional has had to connect to an online platform and directly interact with the participants of the event, whether a conference, meeting or hearing. Suddenly, the reporter has become very visible, and in some cases his or her face or name has even been visible to the other attendants, as seen in the picture below.

What are the consequences of linguistic and social visibility, or invisibility, in the profession? I see two types of effects. Linguistically, less visibility (meaning more sensatim reports) means that the reporter not only omits features of orality and polishes the speaker’s non-standard grammar, but can also attribute words to the speaker which he or she did not intend to use. For politicians, this can be a diplomatic issue which they may not be aware of. For people involved in a trial, consequences can be even harder. Because of this, I see the multimodal report, where the report is synchronised with the audio-visual recording of the event, as the solution to make the most of the reporter’s profession in the future (see Eugeni 2019).

Socially, the reporter has become so visible that he or she can even interfere with the production of the source text: speakers directly address him or her to understand whether they speak properly; participants better realise the intricacies of the profession; and clients understand that the reporter is a real person, not an algorithm. In the end, it is what can be called a “positive fallout”: a positive side effect of an otherwise devastating experience!

Carlo Eugeni is the chairman of the Intersteno Scientific Committee.

References

Eugeni, Carlo (2019) “Technology in court reporting – capitalising on human-computer interaction”. In Ş. Topal and C. Yaniklar (eds.) I. Uluslararasi adalet kongresi Bildiri kitabi, Rize: Recep Tayyip Erdoğan Üniversitesi, pp. 853-861. Retrieved from: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1wbATfxDgaRixgK1LnDJpdiTu2RASkkR5/view (last accessed July 2020).

Venuti, Lawrence (1995) The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation (2nd edition revised in 2008), Abingdon, Oxon, UK: Routledge.

[…] Carlo Eugeni:The reporter’s invisibility […]