Introduction

In an earlier paper in Tiro (Vice 2020), I touched on the question of how official reports can deal with significant non-verbal events. Reporting these events is challenging because official reports are in the first instance (and, in some cases, entirely) reports of the words that were said in a speech event. In this paper, I will explore this topic in more depth. I will discuss some of the solutions to these challenging situations and highlight the underlying assumptions that determine the most appropriate approach an official report can take to deal with them.

There are at least three key assumptions at play:

- What is seen as significant: only the spoken word or non-verbal events too?

- Who is the target audience: those who witnessed the speech event, or people who are reading it without having seen it?

- What is the official report’s relationship to the speech event: as an interpreter of the speech event or an observer of it?

In this paper, I will discuss these assumptions in the light of real examples taken from the official reports of different parliaments.

Just the words: The Congressional Record

The first example is a moving and powerful speech by Bobby Rush in the US House of Representatives in 2012. Rush’s speech is about the shooting to death of Trayvon Martin by George Zimmerman, a member of a community watch group. Zimmerman said he saw Martin and found him suspicious, challenged him and there was an altercation, in which Zimmerman claimed he shot Martin in self-defence. The shooting became a focus for a national debate in the US about racial profiling and self-defence laws.

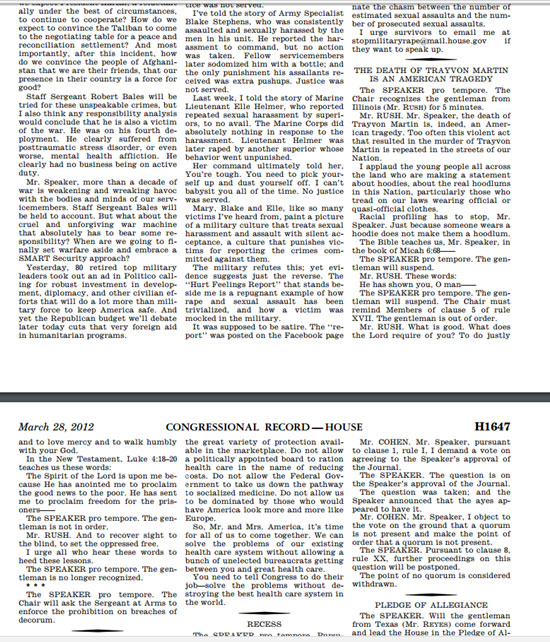

To reveal the assumptions behind ways of reporting this speech, it may help to read the report before watching the video to see how the Congressional Record approached it. The speech was reported like this (Congressional Record 3-28-2012):

The exchange may seem puzzling to a reader who has not witnessed Bobby Rush’s speech: why was Rush told by the Speaker that he was out of order? Why does it appear that the Speaker stops recognising Rush when Rush quotes the Bible? The video provides the non-verbal information—the framing—that explains the Speaker’s interruption:

Bobby Rush starts his speech dressed in a suit but removes his jacket to reveal a grey hoodie. He pulls up the hood and puts on sunglasses. The Speaker and Rush talk over each other, Rush continuing with his speech and the Speaker calling him to order, until the Speaker eventually prevails. Rush was making a point about racially profiling a young non-white man in a hoodie, and in his speech he did this non-verbally and powerfully.

The Congressional Record did not convey this information, for reasons that lie with its underlying working assumptions—I will highlight three of them. The first, which is common to virtually all official reports in one form or another, is that most of the time what is significant in a parliamentary or congressional speech is the spoken word; that is where attention is focused. However, during a speech event a report’s focus could be on any of the infinite number of things that happen while a politician is speaking (see Cook 1990). A second assumption, about the audience, is at play: by not telling readers about the non-verbal information, the Congressional Record assumes that the target audience witnessed the speech event and doesn’t need reminding of the non-verbal framing. With that assumption comes a third about the record’s role as an official report: is the Congressional Record an observer of the speech event, or an interpreter of it? Clearly, in this case it acts as an observer; no interpretation is needed if just the words are being reported.

(Parenthetical description): the French Sénat

Let’s take those three assumptions and apply them to another example, from the French Sénat. This will show a different approach, based on different assumptions.

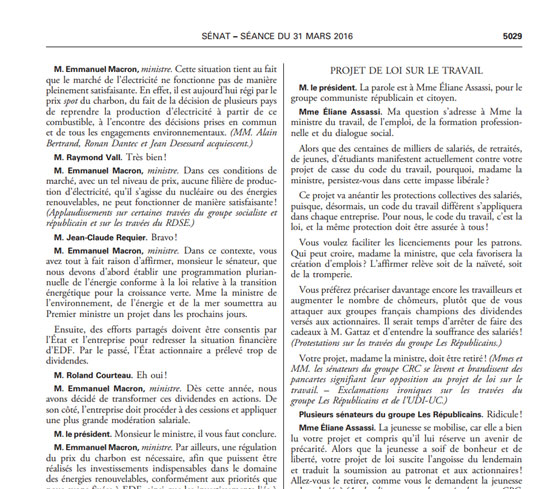

The Compte Rendu report is here:

The report adds an explanation of the non-verbal in brackets (lower right column):

Votre projet, madame la ministre, doit être retiré ! (Mmes et MM. les sénateurs du groupe CRC se lèvent et brandissent des pancartes signifiant leur opposition au projet de loi sur le travail. – Exclamations ironiques sur les travées du groupe Les Républicains et de l’UDI-UC.)

Your Bill, Madam Minister, must be withdrawn! (Senators of the CRC group stand up and brandish signs showing their opposition to the labour Bill. Ironic exclamations from the Republican and UDI-UC Benches.)

Showing the signs is obviously unspoken but they are deemed to be a significant part of the speech event by the French official report—a very different approach from that of the Congressional Record. Likewise, the audience is assumed to be different, and includes people who are reading the report but have not witnessed the speech event and may be unable to watch broadcasts of it and so need pointers for interpreting it. This gives the Compte Rendu a different assumption about its relation to the debate—it is there as an interpreter of the event, not just a detached observer of it.

Tweak the words: The UK Hansard

A third approach to the non-spoken but significant involves making small changes to the spoken words to convey the non-verbal to the reader. This involves a slightly different answer about what is significant, because this approach recognises that significance can sometimes involve the non-spoken. It involves a different answer about the audience, who are not assumed to have been present during the speech event. It also involves some reinterpretation of the event by a reporter, who is not an objective observer of it.

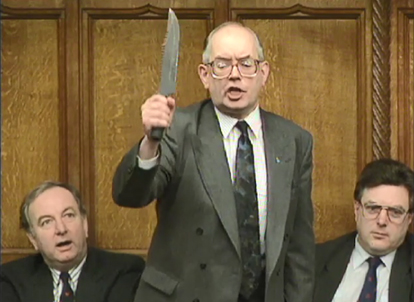

For example, in 1993 a British MP, Jim Marshall, made a speech about banning offensive weapons and brandished a knife in the House of Commons. In his speech, he said: “Is the Minister aware that there are horrific weapons of war widely available in shops in our towns and cities? Will he now introduce legislation to ban the importation and the sale of weapons such as these? Get these off the streets!” and he brandished the knife in the Chamber, as this screenshot shows.

Hansard tweaked his final words, and reported him as saying this (spoken words deleted by Hansard are crossed out, words added are in bold):

Mr. Marshall: Is the Minister aware that there are horrific weapons of war are widely available in shops in our towns and cities? Will he now introduce legislation to ban the importation and the sale of weapons such as these? Get these off the streets! the one I hold in my hand—[Interruption.]

House of Commons Hansard, 3.3.93, cols. 295-6 Commons Chamber – Wednesday 3 March 1993 – Hansard – UK Parliament

This alteration in the words not just acknowledges that it is what is spoken that is significant but alludes to the non-spoken by putting it into words that were not spoken and including them in the report. Again, this acknowledges that the audience may not all have been present at the speech, and obviously requires some interpretation rather than just observation. The risk with such interpretation is of getting the speaker’s meaning wrong.

“Interruption”: a linguistic marker

A fourth approach to the non-verbal but significant is to mark the non-spoken in a way that alerts the reader to the fact that something significant has occurred but without taking the risk of verbalising it.

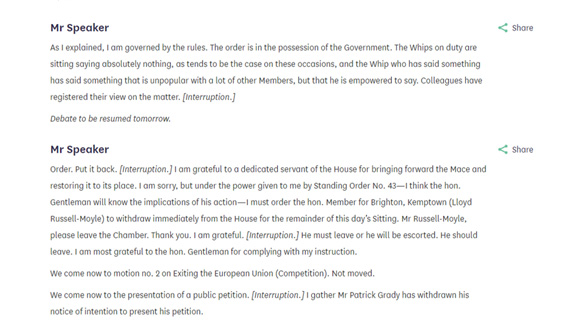

Take the example below of Lloyd Russell-Moyle seizing the Mace during a sitting in the House of Commons in 2018. The Mace symbolises that Parliament is meeting with royal approval and can pass legislation; seizing the Mace constitutes gross disorderly conduct and is a contempt of the House.

Hansard reported the event like this:

“Interruption” is used to indicate that something non-verbal occurred that changes the meaning of what was being said, or the direction of the speaker’s remarks. Ideally, this marker encourages readers to consult the broadcast. Using this approach means the official report can continue to work to the principle that the spoken words are paramount but it allows it to accept that non-verbal significance can be alluded to. It also avoids the risk of having to interpret the event, so may feel a safer option, particularly if the official report team believes strongly that it is an observer rather than an interpreter of the speech event.

My ambition is that the marker “interruption” is reported online and is a live link to the broadcast of the debate. This way readers can click on it and be taken through to the broadcast. However, delivering this for the UK Parliament is harder than suggesting it.

Summary

So when confronted by significant but non-verbal events, at least four approaches are possible:

- To report the words and ignore everything non-verbal;

- To make small changes to the words so they refer to what the reporter deems significant;

- To use parenthetical descriptions to refer to the non-verbal;

- To allude to the non-verbal by a textual convention, such as “Interruption”.

None of these approaches is right or wrong. However, there is consistency with one’s working assumptions, which I have suggested involve at least three elements:

- A decision about what is significant;

- A decision about who one’s audience is as an official report;

- A decision about what one’s relationship to the debate is (observer or interpreter).

Clarity about these issues should make it easier to decide how to report the fascinating examples of the significant but non-verbal in political speeches.

John Vice is the Editor of Debates in the House of Lords, UK. He is also the Deputy Editor-in-Chief of Tiro.

References

Cook, Guy 1990: Transcribing infinity: Problems of context presentation. – Journal of Pragmatics Vol. 14, Issue 1, February 1990, Pages 1–24.

Vice, John 2020: Official Reports and Body Language. – Tiro 2/2020.